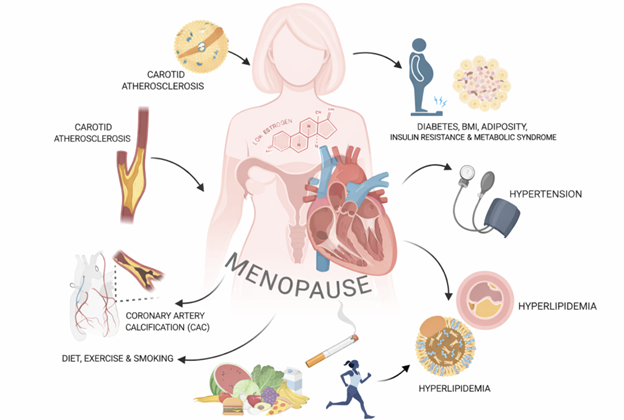

Women’s cardiovascular health begins to decline around age 50. No, it’s not just aging. It’s menopause.

Heart disease remains the number one cause of death among women, yet many women are never told that their risk rises sharply during the menopause transition. Instead, changes in blood pressure, cholesterol, or weight are often dismissed as “just getting older.” The reality is more complex and far more hormonal.

Menopause is associated with several major cardiovascular changes, something I hear very frequently in my practice as Naturopathic doctor with a focus on preventative health in menopausal women. Blood pressure tends to rise, sometimes abruptly. Many women notice new abdominal weight gain, reflecting deeper metabolic shifts including insulin resistance.

A common experience among my menopausal patients is shock at their sudden shift in cardiovascular health. They are eating similarly, exercising regularly, and doing what they have always done — yet their cardiovascular markers are moving in the wrong direction. If you experience hot flashes or night sweats, research suggests your cardiovascular risk may be even higher, making this information especially important.

So what’s really going on?

Hormone changes – specifically estrogen.

As estrogen levels decline, cardiovascular disease risk rises. By the end of this article, you’ll have a deep understanding of how the menopause transition is a significant risk of heart disease for women.

“When it comes to heart disease, women are under-researched, under-diagnosed, under-treated, under-supported, and under-aware.” — Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada, 2018 Heart Report

Keep reading for a deep dive into how menopause can influence blood pressure, cholesterol and metabolic changes.

1. Blood Pressure and Menopause: Why It Rises

Blood pressure does increase with age, but research shows that the sharp rise seen in midlife women cannot be explained by aging alone. One of the largest menopause-focused studies, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), demonstrated that many women experience an accelerated increase in blood pressure around the final menstrual period.

On average, systolic blood pressure increases by approximately 4–7 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 3–5 mmHg during the menopause transition, a change large enough to meaningfully increase cardiovascular risk.

How Estrogen influences blood pressure changes:

- Blood vessel changes: Estrogen influences the health of the endothelium, which is the thin inner lining of blood vessels. Healthy endothelium releases nitric oxide, a molecule that allows vessels to relax and widen. With less estrogen, nitric oxide bioavailability drops, oxidative stress increases, and the endothelium becomes dysfunctional. This means blood vessels are less able to dilate when they need to, contributing to higher vascular resistance and higher blood pressure.

- Arterial stiffness: Estrogen helps keep arteries healthy and ‘elastic’ After menopause, arteries gradually become stiffer. Stiffer arteries cannot buffer the force of each heartbeat as effectively, so systolic blood pressure rises and pulse pressure widens. This arterial stiffness also increases the workload on the heart and accelerates vascular aging.

- Nervous system imbalances: Estrogen also plays an important role in autonomic nervous system balance reflected in higher muscle sympathetic nerve activity and often reduced heart rate variability. In simple terms, the “fight or flight” system becomes more dominant. This shift increases heart rate reactivity, and contributes to sustained elevations in blood pressure.

- Reduced renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAAS) system function: One of the body’s main blood pressure control systems. After menopause, the RAAS becomes more active, promoting blood vessel constriction, sodium retention, and fluid retention. This contributes both to increased blood pressure and to changes in kidney blood flow.

Hormone therapy and blood pressure:

Data from a 2025 review on Cardiovascular risk and menopause (D’Costa, 2025):

- Oral estrogen therapy: Oral estrogen therapy has been shown to modestly reduce systolic blood pressure by approximately 1–6 mmHg.

- Topical estrogen therapy: Transdermal estrogen appears more neutral or favorable than oral. Studies show it can lower diastolic blood pressure by up to 5 mmHg, likely because it avoids first-pass liver metabolism and has less impact on fluid retention.

2. Cholesterol, Lipids, and Your Hormones

Within just one year after entering menopause, many women experience increases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and triglycerides. These changes often occur even when body weight and lifestyle remain stable.

Menopause independently raises total cholesterol by approximately 10–14%, LDL cholesterol by 10–20 mg/dL, and apolipoprotein B by 8–15%. HDL cholesterol may initially rise during perimenopause, but its protective function appears to weaken during and after menopause.

Estrogen plays a key role in cholesterol metabolism. It increases LDL receptor activity in the liver, helping clear LDL cholesterol from circulation. As estrogen declines, fewer receptors are available, allowing LDL particles to accumulate.

Hormone therapy and cholesterol:

- Oral estrogen therapy: Oral estrogen therapy lowers LDL cholesterol by approximately 9–18 mg/dL and raises HDL cholesterol by 15–20%. It also reduces lipoprotein(a), a highly atherogenic particle, by roughly 20–30%. However, oral estrogen can increase triglycerides by 20–40%, which may be problematic for women with insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome.

- Transdermal estrogen: Transdermal estrogen has more modest effects on LDL and HDL but is far less likely to raise triglycerides, making it a preferred option for women with cardiometabolic risk factors.

Insulin Resistance, Weight Gain, and Metabolic Health

Changes in weight and body composition during menopause are not just cosmetic concerns for women, they are deeply tied to cardiovascular risk.

As estrogen declines, women tend to lose lean muscle mass and gain visceral abdominal fat (fat surrounding internal organs and abdominal wall). This shift promotes insulin resistance, a state in which cells respond less effectively to insulin. Postmenopausal women have approximately 40–60% higher odds of insulin resistance compared to premenopausal women, and average HbA1c levels are about 5% higher.

Insulin resistance drives a cascade of cardiovascular risk factors, including elevated triglycerides, lower HDL(good) cholesterol, inflammation, artery health, and accelerated atherosclerosis. Importantly, this can occur even without major weight gain.

Hormone therapy and metabolic health:

Hormone therapy appears to have its most consistent benefits in the metabolic domain, particularly when started early in the menopause transition. Meta-analyses show that hormone therapy can reduce HbA1c by up to 0.6% and lower fasting glucose by approximately 1.11 mmol/L. These improvements are seen even in women with type 2 diabetes.

Hormone therapy is also associated with less accumulation of visceral fat, smaller increases in waist circumference, and preservation of lean muscle mass. On average, women using hormone therapy have a lower BMI by about 1 kg/m² compared to non-users over time.

So With All This Information, What’s Next?

Menopause is a critical window for cardiovascular assessment. Early evaluation allows health care providers to identify rising risk factors before they translate into disease. Naturopathic doctors are especially trained to prescribe preventative health protocols.

Comprehensive bloodwork can assess lipid particles, insulin resistance, inflammation, and nutrient status. Sleep quality should also be evaluated, as untreated sleep disorders such as sleep apnea significantly increase cardiometabolic risk and are more common in midlife women.

Working with a naturopathic or integrative clinician allows for individualized care. While dietary patterns such as the DASH or Mediterranean diets are associated with cardiovascular benefit, they are broad frameworks and do not address individual concerns and risk factors. Precision nutrition strategies and individualized treatment including attention to post-meal glucose responses, gut microbiome health, and hormone management may help mitigate some menopause-related cardiovascular risk.

You May Be at Higher Cardiovascular Risk During Menopause If You Have:

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- A history of preeclampsia or gestational diabetes

- An untreated sleep disorder such as sleep apnea

- A strong family history of heart disease

- Entered menopause before age 45

- A history of breast cancer

- An autoimmune condition

These factors can compound the hormonal changes of menopause and further increase cardiovascular vulnerability.

Conclusion

Menopause is not just a reproductive transition, it is actually a cardiovascular one. Declining estrogen reshapes blood vessel function, cholesterol metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and body composition in ways that meaningfully increase heart disease risk.

Hormone therapy is not a heart disease prevention strategy, but it meaningfully influences the very risk factors that worsen during menopause. Blood pressure, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity may improve depending on timing, dose, and formulation.

With appropriate screening, personalized lifestyle strategies, and individualized care, many of these risks can be identified early and modified.

We Personalize Your Prevention

References

- El Khoudary, S. R., Aggarwal, B., Beckie, T. M., et al. (2020). Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: Implications for timing of early prevention. Circulation, 142(25), e506–e532. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000912

- D’Costa, Z., Spertus, E., Hingorany, S., Patil, R., Horwich, T., Calfon Press, M., Shah, J., Watson, K. E., & Jafari, L. (2025). Cardiovascular risk associated with menopause and menopausal hormone therapy: A review and contemporary approach to risk assessment. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 27, 100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-025-01343-6

- El Khoudary, S. R., Greendale, G., Crawford, S. L., et al. (2018). Menopause versus chronological aging: Their roles in women’s health. Menopause, 25(8), 849–854. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001143

- Samargandy, S., Matthews, K. A., Brooks, M. M., et al. (2020). Arterial stiffness accelerates within one year of the final menstrual period: The SWAN Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 40(4), 1001–1008. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313622

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F., Manson, J. E., Stevenson, J. C., & Fonseca, V. A. (2017). Menopausal hormone therapy and type 2 diabetes prevention: Evidence, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Endocrine Reviews, 38(3), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2016-1146

- Nie, G., Yang, X., Wang, Y., et al. (2022). The effects of menopause hormone therapy on lipid profile in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 850815. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.850815